Bob Peter’s visions realised

The semester system

Teachers Colleges have, in the past, been criticised for a lack of in-depth studies in contrast to the “more intensive” study requirements of university courses. This is somewhat an unfair comparison, since teachers college students are required to master some 18-20 subject areas to meet the demands for graduation as fully prepared primary school teachers. Whereas many subjects in teacher preparation such as: education, educational psychology, English, literature, mathematics, science, history and geography, have much scope for in- depth study, there is also a range of courses which are necessarily limited in scope and challenge. These, must be studied by primary teacher education students to provide them with their skills and knowledge as classroom teachers. Such subjects include: junior primary methods, art/craft education, classroom management, oral English and drama and physical and health education.

Traditionally, in the 1960 and 1970s, university courses focused on two – four subjects for full-time study, and bachelor degrees require a total of nine subject passes for graduation. The usual pattern being: four subject areas in Year 1, three in Year 2 and two major subjects in the final year of study. For teacher education students, to expect the same in-depth study of a much larger number of subject areas would be unreasonable.

To overcome some of the criticisms of the lack of depth and insufficient time for extensive reading in academic subjects, the Principal, Bob Peter, in discussion with his staff at Mount Lawley, opted for a radical change in the teacher education program. Instead of the 30-week program covering all subjects for the whole year, it was decided to introduce a 15-week semester system during which half of the study areas were allocated to half of the incoming cohort (Program A), while the other half-cohort studied the remaining subjects (Program B). This was a radical departure from the Claremont and Graylands Colleges, which continued their 30-week program for a further three years until they also moved over to a semester system. Since courses and delivery times were very much under the control of the Western Australian Education Department and aligned with a four-term school program and school holidays, special permission was sought by Mr Peter and finally granted for him to depart from the overriding control of the Education Department.

Continuous Assessment

In early September 1970, the second semester of the academic year for the first cohort of the new college’s students, still had been progressing in the Bagot Road premises of the Education Department’s ‘Further Education’ in-service centre in Subiaco. Already, the first semester (itself an innovation compared to the traditional ‘three-term’ system matching the WA schools’ timetable) had initiated the ‘progressive assessment’ system introduced by Bob Peter. This incremental system operated on a week-by-week basis rather than the tradition of a couple of assignments during term and a final exam. ‘No exams’ was an early claim for the Bob Peter system of continuous assessment and that was a most effective means of promoting it, especially with the new students.

Of course arguments raged at times but the wisdom of such a dramatic change was based soundly on the new educational psychology and learning theories of the post-war era, especially from the United States, which was Bob Peter’s particular area of expertise. Nevertheless, some staff-members and senior education department traditionalists warned that truly objective assessment of each individual student was only possible within the tightly organised structures of formal final examinations. Only thus, they claimed, could the college be certain that students were actually submitting their own work and that lazy students in group learning situations would not profit from riding on the backs of their more energetic colleagues.

This ignored the fact that under the old systems, not an insignificant number of students had traditionally avoided applying themselves to serious study until the last possible moment in the term and only resorting to last-minute ‘cramming’ in order to ‘fall over the line’. Continuous assessment might prove an anathema to such students but, on the other hand, gave just plaudits to the students who maintained steady pressure on themselves all semester. Once again, this accorded with modern learning theory, derived from the science of psychology. This maintained that learning must be based on the learner’s ever-present ‘knowledge of results’. The analogy of shooting over your shoulder at an unseen target and hoping to improve your aim was used sometimes to argue for continuous assessment.

Course Structure

By introducing a semester system, where the focus is on half the required subject areas, students were able to double the time available for each course, concentrate on fewer subjects and thus eliminate stress due to overload. They could have greater contact with lecturing staff, and obtain more insights in an area of study. In Bob Peter’s words “The student is thus exposed to each subject for a longer period each week, which creates for him a stronger interest. It also reduces the undesirable and confusing effect of too many subjects.”

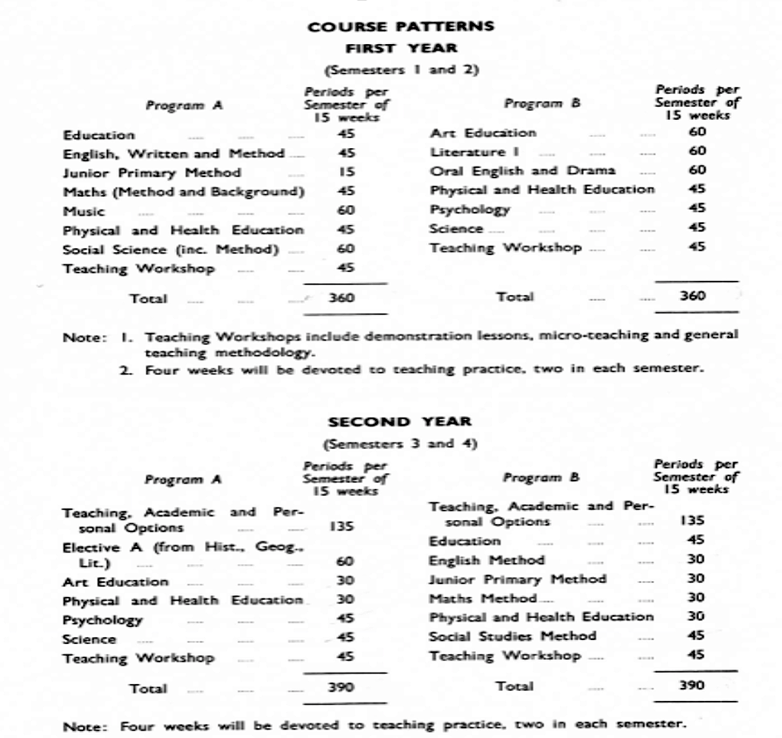

A typical course structure for first- and second-year students was:

The third-year pattern is slightly different because of the introduction of a 10-week Assistant Teacher Program where students work with classroom teachers in schools around the state.

Certification Requirements

For accreditation purposes, subjects were placed in four distinct groups. Each group had a specific significance for accreditation purposes as a classroom teacher, as required by the Western Australian Department of Education.

Group A subjects included Education Theory, Psychology, Education Methods (Junior Primary Methods, Social Studies, Mathematics and English), and Practical Teaching. Students must pass in each of these subjects. In addition, they must also reach a satisfactory standard in Mathematics (Arithmetic) and Written English).

Group B subjects comprised Art-Craft Education, Music Education, Oral English and Drama, Physical and Health Education, Science, Sociology, Literature and Needlework (women only). Whereas all students had to take all these subjects, “compensation, either by credits in other subjects or by overall results in groups of subjects, may be allowed by the Board of Examiners for failure in not more than two subjects, together with any other limitations placed within each group of subjects”.

Group C subjects were introduced to give students an opportunity to follow specific areas of interest by selecting a Teaching, Academic and Personal Option, as well as two Electives of further study in Literature, History or Geography. “Compensation may be granted for one failing subject in this group, providing that compensation is a result of considering the overall results in this group or as a result of a credit in one of the three academic subjects listed in Group A or a credit in one of the subjects of this group. Compensation may not be granted for a failing subject if the mark for this subject is less than D”.

Group D subjects included Games Instruction, General Methods, New Trends in Education and History and/or Geography for students who did not study equivalent subjects at high school. Examination of these subjects is not used for certification, but may be used in assessing the overall results of a student by the Certification Board.

New instructional techniques

Educational psychology, with a focus on instruction, teaching and learning, developed as a specific area of study more suited to teacher education students than the traditional elements of basic psychology. Particularly in the USA and also in the UK, traditional psychologists applied the principles of motor development, cognition, motivation, emotional, social and personality development to child development, teaching and learning within the classroom. From the early writings of Ralph Tyler (1949), Benjamin Bloom (1956), and Jerome Bruner (1961), educational psychology became in its own right an important component of teacher education courses. Consequently, major advancements were taking place in instructional design and in teaching/training technologies. Together with the growing importance of electronic calculators, computers and “teaching machines”, the use television, in particular, grew as an important aide in classroom teaching.

The Foundation Principal, Bob Peter felt “that it is increasingly important for the teachers colleges to use methods which it advocates that its students use in schools. This means in part greater reliance upon developments in educational technology”. From the initial planning stages, Bob Peter and his team of selected staff, worked closely with the architects from the Public Works Department to design an open, flexible building structure, with large theatre-style lecture rooms, open-area classrooms (which can be transformed into smaller spaces), flexible tables and desks for individual or group discussions, small tutorial rooms, science laboratory spaces, functional art and craft buildings, and a one-way viewing laboratory for child development and a gymnasium.

With the focus on modern teaching and training needs, the centre-piece of the new college was the specially designed media production building. Here, the telecine system provided for the production and telecasting of high quality 16mm cine film or video productions. Lecture theatres and all classrooms were equipped with television monitors and the reticulated closed-circuit television facility could be used at any time by calling the control centre and the video or slides would be sent to the monitors. The media centre was also used to train students in media design, development and production in preparation for their roles in future classrooms.

Using this new technology, micro-teaching became an integral part of teacher education. Here students were filmed on their delivery and performance in presenting a short lesson to a small group of children. They were able to replay the lesson immediately, analyse their performance, obtain feedback from staff and fellow students and discuss issues, which can be improved upon.

Face-to-face lecturing in conventional classroom groups became a thing of the past. The need to repeat the same lecture to different groups was replaced by a mass lecture followed by two-hour tutorial/laboratory/workshop session. During these sessions, the principles learnt in the mass lecture were analysed, discussed and evaluated in small cooperative learning workshops or presented by students in tutorial sessions. The focus was on students doing the learning, not just listening to the lecturer. The students used all college resources available to find solutions and solve problems.

Therefore, the Educational Resource Centre became a central part of student learning. This centre was more than just a library, it was expanded to provide multi-media learning facilities, including self-instructional learning laboratories as well as material resource centres where students could borrow 35mm cameras, video cameras, audio taping facilities, teaching aids and a wide range of educational charts, toys, games, objects and instruments that they could use while on teaching practice.

Continuous assessment throughout the teacher education course replaced the single examination at the end of the semester. In Bob Peter’s opinion, the end of semester exam or “day-of-judgement” gave rise to cramming, “question spotting” and a great reliance on memory and it never sampled the students’ understanding of the whole course. So, students’ assessment was continuous throughout the semester and based on tutorial presentations, short tests, assignments, reports, essay writing and portfolios.

Although it was a novel development and made students work throughout the semester, soon it was felt that students were working full-speed all the time and had very little opportunity for incidental discussions and reading for pleasure. In Education Studies for example students were required to present three tutorial papers, write three laboratory reports, pass four tests and satisfactorily complete three worksheets. Fortunately, common sense prevailed and in later years the load was reduced to a more tolerable level.

Student personal development.

In the new college there was a great emphasis on independent study assignments, elective studies and the use of all forms of multi-media instruction. The college had an “open door” policy where students could see staff whenever there was a need. This added to the focus on students’ personal development and their duty of care. Thus, each staff member was assigned to a special home tutor group (maximum 16 students) which met for one hour each week to listen to students’ concerns, provide advice and implement ways of helping them where required. Students were also encouraged to participate in team sporting activities, sports carnivals, local and inter-state sport and debating teams and in a variety of science, maths, music and drama groups.

Integration of theoretical courses with practical teaching

Right from the planning stage, it was the Principal’s vision to close the gap between theory taught in the college and the practical realities in the classroom. Thus he insisted on a very close cooperation between subject departments and an effective integration of Educational Theory with Educational Psychology and Teaching Practice.

This was achieved through regular teaching workshops with demonstration lessons, general methods and micro-teaching. The Teaching practice Preparation Week, where all academic programs were suspended, became a very valuable time for students to prepare their lessons and ask for help or ideas from lecturing staff. The Music, English, Speech and Drama, Social Science and Mathematics departments provided specialised methods courses to help students refine their teaching techniques.

Throughout their three-year training course students were assigned to four weeks of Teaching Practice (two weeks in each semester) for Years 1 and 2 and fourteen weeks (in one block) of teaching practice in the “Assistant Teacher Program.” During these practice weeks students were regularly visited by college staff to evaluate their performance, discuss issues with the student and school teaching staff, and to assist where there was a need for remedial work.

Student involvement in policy and decision making

“The final point of departure from established practice at Mount Lawley was the degree of student involvement and participation in the running of the college. It has long been accepted by industry that employees, given the chance to participate to some extent in management, are more effective workers. At Mount Lawley, it was hoped to promote maximum staff-student cooperation by greater involvement of the latter in decision-making.”

The Student Council was established as a formal body to deal with student affairs and members of the Student Council were represented on the Courses Sub-Committee, the Publication and Research Committee and Campus Affairs Committee. The latter was chaired alternatively by a nominee of the Student Council and an elected staff member. Bob Peter had strong belief that students should have a say in the administration of the college.

Student government

Another area of innovation was student government. In the previous teachers colleges there was certainly participation by members of the college student councils in many aspects of the sporting and entertainment programs of Claremont and Graylands colleges. Student publications (newsletter- newspapers, and college annual magazines) were a great place for communication skills to be learned and creativity to be exercised in literary and other artistic forms. But it could be said that these were based on the ancient traditions of school prefect systems and closely supervised cultural activities that had no origins in really democratic processes. The new era of teacher education embraced in WA by the Mount Lawley Teachers College saw student government take a major forward step in a participative process of decision making, including buildings and grounds development, media and book repositories, staff appointments and many financial decisions. The MLCAE, which succeeded the teachers college under its Education Department jurisdiction in 1974, gave even greater scope for students to play a part in the running of the new semi-autonomous ‘College of Advanced Education’ and to determine its future directions.

As previously mentioned, in the architectural planning of the Mount Lawley Campus generous provision was made for accommodation for student government and supporting student services. In these early days of the expansion of the tertiary education sector the student associations were able to collect compulsory student fees, which provided the student association with reasonable funds to support sporting clubs, and other recreational, social or educational organisations for students. In the broader context it was possible to foster student publications, inter-institutional sporting, drama and music competitions and interstate educational tours. Until certain political parties in Australia successfully opposed compulsory student fees, there was ample evidence that an intensive college student government experience was potentially a great additional aid to the general education of the future students who graduated from the Mount Lawley Campus.

Student accommodation.

A question facing every tertiary education student in Western Australia for the past 100 years or more has been whether to be in residence on campus or to attend on a day-basis. As mentioned already, Claremont College, like many such training institutions replicated the ecclesiastical origins of tertiary education in Europe and Britain by allowing students to ‘live-in’ while training (possibly to ensure the safety and of the female students, as nuns are kept morally secure in a convent). Even at the time Mount Lawley campus was established, a female graduate teacher on appointment to a teaching position was required to resign from her post if she changed her status from single to married. However, by 1970 it had been many decades since its elder sister, Claremont College, provided its female and male students with separate on-campus accommodation. Yet two-thirds of the students expected to enrol at Mount Lawley would be female. This reflected the ratios of women to men teachers in the primary teaching service of Western Australia in 1970 but also reminds us that, at the time, only nursing and teaching were professional avenues for full-time careers for women.

An important entry in the first Mount Lawley ‘Calendar’ in 1970 mentions plans for the reintroduction of female student accommodation in the building plans for the campus:

‘Included on the campus will be a student hostel, initially for 60 women students; provision has been made for another unit of the same size for women and one for 60 men should funds become available. The student hostel will share recreational and dining facilities with the rest of the college.’

In those days hostels for the state government high schools were managed and financed by the WA Country Hostels Authority. This gives a clue to why the Government anticipated funding of its proposed hostels at Mount Lawley campus would be forthcoming—primary school teachers had always been recruited in significant numbers from the West Australian country senior high schools, which in those areas could give a five-year secondary school education, the basic qualification for acceptance into teacher training. It is possible that the Second World War increased the State’s dependency on female teacher recruitment and this in turn increased the percentage of female teachers in these training institutions.

Proof of the above intentions to provide the Mount Lawley campus with hostels remains to this day. There are still unfinished covered walkways leading in the direction of these hostels, although the campus library eventually took up one intended location. Why the hostels were never built is another story. Ironically, many years later, in 2008, the Edith Cowan University did build its Student Village accommodation on the campus and so the hitherto denied residential era of the campus was finally begun.