Planning, designing and building the new college

In the early 1950s the Western Australian Government appointed a well-known, overseas town planner to prepare a plan for the future development of the Perth metropolitan region, the surrounding emerging suburbs, and beyond. Professor Gordon Stephenson was invited to act as the major consultant for the project. Stephenson was well known for his work in planning and construction within the “British Isles during and after World War II, notably Lord Reith’s Reconstruction Group and with Sir Patrick Abercrombie for the Greater London Plan. Later he was appointed Professor of Civic Design at the University of Liverpool and in 1952 he chaired the Dublin National University Planning Committee” (Renner & Jongeling, 2016, p. 14).

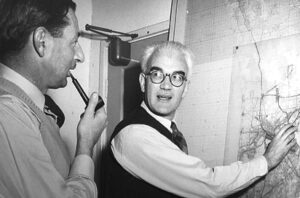

Stephenson joined with the newly appointed Perth Town Planning Commissioner Alistair Hepburn to outline a vision for development of Perth and Fremantle and surrounding areas for years to come. They proposed a corridor type of image comprising of several hubs around the central city and connected by well-designed major roads and railways.

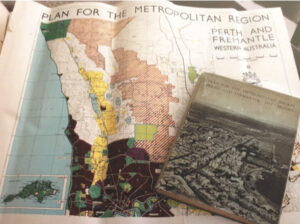

The Stephenson-Hepburn Plan, published in 1955 became a reference for a sequence of follow up studies and reports endorsing the establishment of new hubs, roads, railways, hospitals, high schools, technical schools and colleges, teachers colleges, private schools as well as recommendations for land use and recreational areas (Government of Western Australia, 1955).

The Stephenson-Hepburn plan made a significant contribution to the focused development of the Perth and Fremantle regions and the establishment of major suburban areas such as Ellenbrook and Joondalup. The plan also included a proposal for three new teachers’ colleges, “the main one on a site already selected on Pelican Point, where it would be adjunct to the University, and others on the Mount Lawley and the Collier pine plantations” (Government of Western Australia, 1955, p. 208). The arrow in the Plan, clearly indicates the position of a future Mount Lawley Teachers College. This was in 1955 when the recommended site was still a pine plantation on a low lying, flat swamp lands, although most of the pines were destroyed in a huge bush fire on 14 April 1950, and before that a city refuse dump and sanitary depot. Because of its sensitive environmental position, the site for a new college at Pelican Point was later changed to the Corner of Hampton Road and Stirling Highway for the building of the Nedlands Secondary Teachers College in 1969, while the proposed site at the Collier pine plantation became the now Curtin University.

Although allocated a substantial area of land in 1955 within the Mount Lawley pine plantation, it was not until the early 1960s that the government focussed its attention to building new teachers colleges. This can be attributed to rapid growth in primary and high school enrolments and the release of the Martin report in 1964 as discussed in Chapter 1.

Thus, Mount Lawley Teachers’ College began to emerge as a government planning concept around 1964. In part it was intended to serve those rapidly expanding numbers of Western Australians but especially the prospective teachers located in the new 1970s suburbs stretching north from Perth City to Wanneroo. There was also a population explosion eastward from Morley to Midland and into sections of the Darling Ranges.

By 1967 the Public Works Department had appointed Mr Stan Hewitt, as Mount Lawley College project architect, to consult with Mr R G Peter, the then Principal of the Graylands College. Their task was to begin planning for a campus in the former Scadden Pine Plantation of Mount Lawley, adjacent to the existing Mount Lawley Senior High School.

Tradition and conservatism had to a greater or lesser degree overtaken the Claremont Teachers’ College long since its foundation in1902. Graylands College, in its post World War II Migrant Camp, was more restless and new ideas were being tested by a young and vigorous college staff looking for a different approach to preparing classroom teachers.

Under Bob Peter’s inspiring leadership, they had their chance. Bob (as he was always known) set up multiple planning committees selected from key members of his Graylands staff to be the academic advisors for the conceptualising of the new institution for primary teacher training.

Situated on the corner of Alexander Drive and Bradford Street, this newest teacher education campus project was conceived from the outset by Bob Peter (supported by the Director of Teacher Training, Neil Traylen) to be based on progressive, even reformist principles. Naturally enough these aspirations also contributed to the architectural design. The new campus in Mt Lawley, and its facilities were to be laid out as a cluster of specialist complexes.

On the north boundary there already existed the Mount Lawley golf course and the National Safety Council driver-training centre. To its immediate south already a large section of the proposed campus had been excised for a housing development, thus somewhat cramping the future teachers college into a mere 28 acres. The open plan or grid-layout of the college was something of a breakaway from the monolithic model of a teacher training institutions in Australia.

These had imitated many traditional teachers’ colleges in Britain. Usually, such colleges had vaguely ecclesiastical and neo-Gothic elements and obvious associations with stately (or not so stately) homes converted to more mundane uses. Such edifices, having emerged during the rampant ascendancy of commercialism in the nineteenth century, provided an emphatic authoritarian focus for turning out new teachers for compulsory schooling—‘like so many table legs’ to misquote Charles Dickens in Hard Times.

Claremont Teachers College in 1902 had been no exception to its British counterparts, with its impressive sandstone portico and steep gables, flanked by a sweeping driveway and forecourt. The impressive entry space was ample enough for a carriage and horses to draw up in front. And sweeping down towards the Swan River was a greensward perhaps suggesting landed gentry ownership and maybe faint memories of the classical estate designs of ‘Capability Brown’.

By contrast, the new Mount Lawley College campus was conceived according to a modernist and ‘progressive’ philosophy to be an ‘open plan’ grid of dispersed buildings providing the accepted contemporary specialist study areas such as education and psychology, science and mathematics, media studies, art, physical education, English, languages and the humanities in general. As well there would be provision for a separate student government building, not only as a gesture to democracy but perhaps also as a training ground for a much more student- centred educative process. Traditionally in the West, many primary school trainee teachers were recruited from country areas, so the campus building plans also included hostel accommodation for women and men students and generous catering facilities in a refectory building.

Of course, a library was planned to be central to the campus but incorporated within an entirely new concept, to be named the Learning Resources Centre (LRC). This centre would be based around a CCTV production facility and a communication hub distributing teaching programs via suspended TV monitors to every campus teaching space but especially to the large and small lecture theatres. It also serviced the brilliant new training technique for budding teachers that was termed ‘micro-teaching’. An orthodox book library would be supplemented by the newly emerging audio-visual materials, especially video-tape cassettes. These materials were intended to be listened to or viewed in the specially built carrels in the LRC or in ‘computer laboratories’ with provision for group listening or viewing (e.g. for foreign language studies’ students).

Micro-teaching as an additional facility for instruction, especially in practical teaching, was to be the ‘mini-classroom’ whereby students in special enclaves of larger classrooms could video-record a lesson for viewing by fellow trainee students via a one-way screen. Then, the student teacher could make subsequent analysis of the videotape with staff-members and classmates. This required new and unique architectural provisions in the design of the campus buildings. Therefore, the development of the Mount Lawley campus was a very significant departure from the temporary and often piece-meal adapted accommodation for growing numbers of student teachers being provided all over Australia consequent to the post-Second World War Australian population growth.

Graylands College in its un-lined ex-military and migrant camp corrugated iron huts had been just such a provisional campus, yet lasted for several decades—as hastily arranged accommodation often did. Yet a positive outcome of that relative privation was that the academic planners for the new Mount Lawley Teachers’ College were

almost entirely drawn from Graylands staff, whose emergent new vision and exuberance were well fitted to being extraordinary ‘agents of change’ for the Mount Lawley move.

They had unusual opportunity to also enhance the Public Works architects’ brief, even to the extent of making scale models of specialist buildings. The actual buildings frequently embodied these recommendations in amazing detail, as Bob Peter once recalled in an interview with an ex-staff-member, Bob Rogers.

Thus the plan for Mount Lawley was conceived to be a quiet revolution in the concept of teacher education from the ground up. Many of the existing teachers’ college staff for years had endured criticism, by colleagues in the university sector, of their academic standards and practices. Ironically, in those days, the majority of university staff had no teaching qualifications or training themselves. Lecturers appointed to the expanding teachers colleges often were a somewhat younger group of tertiary teachers, including ex-servicemen, who had recently gained degrees in Australian universities.

Such recruits were maybe capable of keener insight into the deficiencies of instruction in the time-honoured traditions of teachers’ colleges—a multiplicity of subjects in the curriculum —up to twenty five— studied largely simultaneously over a two-year period and rarely studied at depth. Teachers college students traditionally had not always been recruited for their intellectual prowess. It is possible that such younger college lecturers were able to seize even more fiercely the chance to revolutionise a new era of postwar teacher education. This was especially so of those who had been recently appointed to the Graylands staff.

Interestingly, back in 1948, Bob Peter had himself conducted a long-ranging experiment to monitor teachers’ college graduates in their first years of teaching and he now knew what personal abilities lead to successful teaching careers for them.

With the impending 1970 break-away from Claremont College (with its 1902 origins), Bob Peter therefore had, in the new Mount Lawley institution, a source of excellent personnel with whom to plan and effect significant change.

Initially, Claremont College had kept those younger Graylands staff closely in check, insisting that the parent college set their final examinations and so effectively controlled the syllabus. By the late 1960s, however, the newer staff-members were growing restless at Graylands. Wherever possible, more modern textbooks were slipped into the lists. Creativity in students was rewarded in approaches to course submissions and this was further encouraged in recreational camps, student drama, art exhibitions and publications—emphasising extra-curricular activities and more informal staff-student relations. It was still obvious that, compared with the university sector, ‘teacher training’ (as it was then still known) lacked academic freedom and a healthy mix of contact with other professional training areas such as law, engineering and agricultural science. Hopes for progress were indicators of the aspirations, still some years away, for changes in those WA institutions, which remained constrained just to preparing teachers.