Aboriginal Higher Education and Other Programs – Leading Australia

From 1974, Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education (MLCAE) became the leader in Australia as the most comprehensive and innovative programs in Aboriginal Studies and Education, but the triggers of the initial action, were far from admirable. Two separate and serious complaints were brought by parents of graduates to Charles Staples, Acting Principal of the then Mount Lawley Teachers College early in 1973, claiming that the College had failed in its duty by not adequately preparing these two graduates for their first teaching positions.

One graduate had been appointed to teach in remote Aboriginal community and the other in school in a town with a significant Aboriginal enrolment, both in the far north of WA. As a result, one graduate was about to resign, and the other had what was then known as a nervous breakdown, both having suffered culture shock and feelings of extreme professional inadequacy.

One set of parents were planning legal action against the College, and the other set was discussing a story in the media, unless the College could demonstrate that preparation of these new graduates had been adequate for Aboriginal education. Two tragic situations for the graduates and their families, and potential damage for the College in terms of public reputation and financial costs, summed it up. MLTC was part of the Education Department of WA, so the WA government was involved in the complaints.

Charles Staples discussed his deep concerns about these complaints with John Sherwood, who three months earlier had taken up the College’s first lectureship in Anthropology and Sociology in the Department of Social Sciences in the College. Neither knew of any significant component of the Diploma of Teaching preparing students to teach in predominantly Aboriginal schools and communities, or Aboriginal children in other schools throughout WA.

A major prevailing policy underpinning teacher education at that time was that of generalised content, in which the one standardised course was regarded as sufficient to prepare every student teacher for every classroom in Western Australia, regardless of context and demography. This “generalised” teacher education was a clear case of one size fits all. There was virtually no specialised training offered in teacher education courses, to equip students to teach in unusual situations across WA.

Charles Staples requested John Sherwood, as a matter of urgency, speak to every Head of Department, and report back with a statement of every component of the College’s three year Diploma of Teaching, which helped to prepare students for schools with a significant Aboriginal populations. The report was brief and disturbing: there was not a single compulsory lecture or assignment for all student teachers, on teaching Aboriginal children, or on sensitivity to their culture, languages, history, and circumstances.

Apart from a few lectures and one future assignment on Aboriginal culture in the new Anthropology course, little else within the College could be considered preparation of all students for Aboriginal education. Occasional optional assignment topics on Aboriginal issues only affected a small percentage of students, who opted for these. The vast majority of students had no exposure to any content to prepare them for teaching Aboriginal children, or relating to Aboriginal communities. John Sherwood agreed to develop a plan to remedy this situation.

In the most fortunate timing, just four months earlier, in December 1972, the Whitlam Labor government had been elected, and immediately fulfilled an election promise: to set up Australia’s first Commonwealth Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA), with a large new budget which did not exist previously. In a phone call to Tom Roper, the Minister’s Advisor on Aboriginal Education, John Sherwood explained how the college wanted to significantly improve its preparation of student teachers for Aboriginal situations, and was told, by Tom, that because this was among the highest priorities of the new DAA, it was opportune to submit a brief submission as soon as possible.

With the strong support of Charles Staples as Acting Principal, a submission for a comprehensive Aboriginal Teacher Education Program (ATEP), consisting of many projects, was submitted to DAA, in April 1973. The amount requested was $125,400, which was huge at the time. It aimed to produce the appropriate education of a maximum numbers of teachers of Aboriginal children, both pre-service and qualified, in the minimum time, as well as starting research and resource development considered necessary for such education. The submission requested funds for six full time staff, travel, purchases, publications and media projects and more.

Line items in the original submission, were for General Administration and Contingency, Tandberg Language Laboratory, Postgraduate Course, Undergraduate Course, Audio-visual Materials (purchases and productions), Printed Publications, Research and six Staff Salaries and on Costs.

When the Principal, Bob Peter, arrived back from leave, in July 1973, he was not pleased with the submission, claiming it was too ambitious, and would “make the College the laughing stock of tertiary education in WA”. This frugality, reflected his background in the state Education Department rather than the new socio-political environment of higher education in Australia, particularly Aboriginal Affairs.

He suggested that the submission be re-written, cut back substantially, and re-submitted. Fortunately this did not happen, and within a month or so, he received a phone call from DAA saying the submission had been granted in full, with at least equal funding for the following two years, probably more. He was then concerned about how this huge and unusual grant would be administered by the college.

It funded the employment of six full time staff, the creation of new undergraduate and postgraduate courses, purchases of equipment, frequent travel all over Australia for staff and students on placements, research, publications, multi-media productions, and involvement of Aboriginal people in all aspects of ATEP. The written approval of the DAA grant to establish ATEP was received by the college, in September 1973.

Lyall Hunt, Head of the Department of Social Sciences, argued that ATEP should be part of his department, but the Principal, Bob Peter, became convinced that a new interdisciplinary department separate from any existing one, would be more appropriate for managing the complex program and liaising with all other departments and Aboriginal communities. He appointed John Sherwood as Acting Head of ATEP as soon as the funds were received (September 1973), and John immediately advertised for five staff nationally.

On 26 November, 1973, Mount Lawley Teachers College became an autonomous institution called Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education (MLCAE), independent of the Education Department of WA, giving ATEP staff more freedom in developing new courses. This was the “Appointed Day” under the Teacher Education Act 1972. After a national advertising campaign, five new ATEP staff commenced during January 1974, and new undergraduate and postgraduate courses began the next month, the latter by external studies.

The nature of Mount Lawley Teachers college as a new, innovative training institution, and its raised status as a College of Advanced Education was of great assistance to ATEP in introducing many new projects. The Senior Executive gave ready support to every project in the original funding submission, as well as to new projects proposed by ATEP and approved by DAA for funding. If it had remained part of the Education Department of WA, it is unlikely that many approvals would have been given.

This was a magnificent achievement for the three newly appointed lecturers, John Bucknall followed in 1976 by Neville Green (Aboriginal Education), Carole Reed followed by Lois Tilbrook (Anthropology) and Neil Chadwick followed by Eric Vászolyi (Linguistics).

In their first two months they had to not only settle in and prepare lectures for classes on campus, but also prepare external studies lecture notes for the next two months, and so on for the rest of the year.

ATEP Publications and Media Officer Ed Brumby produced the external studies packages to be posted to students around Australia, mostly in remote schools.

Aboriginal involvement was deemed essential from the outset, particularly because the college did not have any Aboriginal staff or board members within it. An Aboriginal Advisory Committee, comprising senior members of the Aboriginal community, was established, in 1974, to guide the development of ATEP, evaluate its progress, suggest modifications where necessary, and recommend new initiatives. From 1975, it interviewed and recommended candidates for the Aboriginal student group intake. Early members of the Aboriginal Advisory Committee were May O’Brien, Norm Harris, Cedric Jacobs, Joyce Trust and Rob Winroe.

This involvement was broadened through Aboriginal guest speakers from all parts of Australia speaking to students, and undergraduates having all three of their placements of teaching practice, totalling 14 weeks, in predominantly Aboriginal schools throughout WA and parts of the NT. Field trips were conducted to rural and remote areas to broaden experiences for students with Aboriginal people, culture and country. Some of these trips were to Mullewa, Cue, Kalgoorlie, Leonora, Laverton, Jigalong, Carnarvon, Port Hedland, Strelley Community, Narrogin and Gnowangerup.

ATEP was the largest, most comprehensive and innovatory program in Australia in Aboriginal higher education, from its inception in late 1973 until the late 1980s. The National Aboriginal Education Committee (NAEC) developed a special relationship with ATEP, and developed the “Thousand Aboriginal Teachers by 1990” target for Australia, based on ATEP’s achievements in dramatically increasing the number of Aboriginal teachers in WA, through its Supported Group Intake model. A few tertiary institutions such as Torrens Teachers College (SA), Batchelor College (NT) and Sydney University (NSW) offered smaller, less extensive projects, but ATEP was unique in its scale, comprehensiveness, diversity and multi-project nature. Over the decades, most universities adopted some of the ATEP projects, especially the Supported Group Intake of Aboriginal students, and the Aboriginal Student Centre on campus.

Recognition of the innovative projects and their significant outcomes is reflected in the following excerpt from the college’s Annual Report for 1974, p.26.

In addition to Australia-wide experience gained prior to appointment, staff concerned have travelled widely in the course of the year. The experience so gained has noticeably influenced College courses and enriched the quality of teacher education for Aboriginal School situations. Such study trips embraced interstate conferences and tertiary institutions, the Kimberley, the Pilbara, the Goldfields and Western Desert Region.

Aboriginal Education is developing rapidly at national level, and the future involvement of this College is difficult to predict. However, at this time it could involve extra undergraduate programs to allow different degrees of specialisation, expansion of courses to include recently developing areas such as cognitive development in Aboriginal children, admission of a group of Aboriginal teacher trainees, and the introduction of new courses in Intercultural Education.

Recognition at the national level resulted in two staff members being awarded national honours, for work mainly in the 1970s and 1980s. John Sherwood was awarded an Order of Australia Medal (OAM), in 2017, “for services to Aboriginal education”, mainly through Mount Lawley and Bunbury Campuses, and Neville Green received a Member of the Order of Australia (AM), for his varied historical research and publications, some of which were from his work in ATEP.

Undergraduate units – Major, Minor and Electives

The most urgent aspect of ATEP was to design and begin teaching units in the Diploma of Teaching, to prepare student teachers for Aboriginal education, in different proportions of their course. Twelve units were written and approved for a Major in Aboriginal Education; six made up a Minor, and other students could take one or two as electives. Five teaching practice placements were organised for Majors and Minors in schools having significant Aboriginal enrolments, all over WA and some parts of the Northern Territory. These consisted of two each of two weeks in years 1 and 2 and one of ten weeks in year 3, all in different schools, supervised in school classrooms by staff from ATEP and other departments, in visits to the schools. Each year, Major and Minor students went on field trips to Aboriginal communities, to experience rural and remote life, and to learn about Aboriginal culture on country. ATEP staff and Aboriginal guests spoke to students in classes run by other departments, to increase exposure. ATEP was a first in Teacher Education in Australia, in its scale and comprehensiveness, and over the years produced hundreds of graduates with a specialisation in Aboriginal Education.

All teacher education students could apply for teaching positions a few months before the end of their course, and those with Aboriginal Education majors and minors usually stated preferences for either remote Aboriginal communities or remote towns, or predominantly Aboriginal schools in less remote towns. In most cases, their preferences were agreed to by their employer, whether the Education Department of WA, or Catholic Education Commission, or other employers.

Stephanie Crowe (nee Waller, 1974-6) was reading the West Australian newspaper at home in Albany late in 1973, and saw a small advertisement about the new ATEP course starting at Mt Lawley CAE the following year. She enrolled, and thoroughly enjoyed the Aboriginal Education major, especially the field trip to the goldfields with John Bucknall and teaching practice placements in Wittenoom and Kalumburu. In her 60s now, she is still doing relief teaching in remote Aboriginal community schools.

She writes:

“These were amazing experiences and just made me more excited about getting away from the city. The historical perspectives completely opened my eyes as to the past treatment and behaviours of the dominant culture. I enjoyed completing research and the seminars where we all got to share ideas and interpretations. My first posting was to Roebourne Primary School, where I stayed for 3 years. I have since taught at Looma, Bayulu, Ngalapita, Muludja, all of the Ngaanyatjarra Lands schools, Tjuntjunjarra and Wiluna.”

“The ATEP course gave me some insight into the some of the issues facing aboriginal people and as a teacher, I felt I was in a position to make a positive contribution to a child’s school experience. I have made many good friends in remote locations and some I still keep in touch with. If I hadn’t have enrolled in the ATEP course, I would not have gone into teaching.”

“It was quite a progressive course to add to MLTC subject curriculum and long overdue. To acknowledge that prospective teachers do want to work in remote communities with Indigenous children and adults, was pretty out of the box thinking. And to provide these pre-service teachers with some background knowledge.”

Dr Helen CD McCarthy (1978-80) heard about the Dip Teach majoring in Aboriginal Education from a friend already enrolled in the course. Highlights were the field trips to Devils Lair near Margaret River and the red ochre mine at Wonga Maya near Cue, with Neville Green, and being able to learn the desert language Wangkatja with Eric Vászolyi. She taught in Angurugu, Numbulwar, Umbakumba, Milingimbi, Ramingining and Batchelor College in the Northern Territory.

She writes (2012, p.1)

“I studied primary teaching, majoring in Aboriginal Education which enabled me to complete my pre-service teaching practices in remote Aboriginal schools in the Pilbara and Kimberley regions in Western Australia. In addition, every year one of our lecturers would organise awesome field trips to places of significance. Off we would go in the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program bus, all fifteen of us, out east beyond the city to the desert and the ancient ochre caves or down south to the kitchen midden mounds and rock art sites. As a graduate I believed my lecturers had inculcated me well and that my time spent in this rich context allowed me to grow even more deeply respectful of the multifarious Aboriginal ways of being and their attendant knowledge systems.”

These reflections of Steph’s and Helen’s experiences show that they were given preparation to immerse themselves for their whole careers in Aboriginal education. Like many students majoring in Aboriginal Education in their Diploma of Teaching, the names of the schools in which they did teaching practice, or later were appointed to as teachers, are totally unknown to almost all West Australians. They had absolutely unique, life changing experiences.

Mention must be made of two very unusual and innovatory teaching practice placements. After considerable staff debate in 1975, three second year Aboriginal Studies students were approved to do their placements at Strelley Station, which did not have any schools at the time. They were to offer education to about 100 children, and assess the potential for a future bilingual, bicultural achool, John Bucknall supervised the unusual teaching practice placement, and had discussions with leaders about applying for funding for an Aboriginal independent school with annexes on several stations. This experiment was extended the following year, 1976, when the above three students did their ten week Assistant Teacher Program in Strelley School which had started only a few months earlier.

In the second innovatory placement, in 1976, Mark Chambers was approved to spend all 10 weeks Assistant Teacher Program in the middle of his 3rd year in Jamieson and Blackstone, two Aboriginal communities beyond Warburton Ranges, with no school or housing or other infrastructure. His placement was to give children whatever education he could, in the circumstances. He continued his links with the community for many years, becoming very fluent in Ngaangatjarra, the local language.

These were two additional examples of how open to ATEP’s innovatory proposals Mount Lawley College was. See below for further descriptions of Mount Lawley’s links with Strelley Group of Communityy Schools.

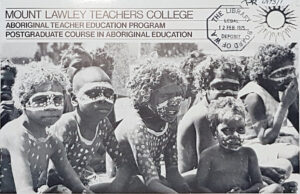

Postgraduate Course – Graduate Diploma in Aboriginal Education

Another urgent need was a course for teachers already serving in Aboriginal school situations, because almost none of these had any training for Aboriginal situations. This would make more immediate changes in the teaching of Aboriginal students than the pre-service undergraduate units, because the teachers could apply what they learnt on the spot, unlike the student teachers who had to wait up to three years before graduating to a classroom.

The Postgraduate Course in Aboriginal Education (GDAE), was offered only by external studies, to enable hundreds of practising teachers all over Australia to complete studies, while living and teaching in communities. This was the first such external course in Australia, giving teachers professional knowledge, skills, networks and resources for teaching Aboriginal children and adults. Planned, operated and taught entirely by ATEP, this was MLCAE’s first external studies course, and was of immense value to teachers who were in challenging situations which they had not been prepared for. In about a year, the course had been accredited nationally as a Graduate Diploma in Aboriginal Education (GDAE).

The following advertisement from the Education Department of WA’s Education Circular outlined the course and called for enrolments from teachers.

Aboriginal Education, 1975

External Studies Enrolments Invited

Qualified teachers are invited to apply for enrolment in the Postgraduate Course in Aboriginal Education at Mount Lawley Teachers’ College, Western Australia. The course is one aspect of the comprehensive Aboriginal Teacher Education Program established earlier this year at the College, and in 1974 enrolled nearly 60 teachers, mainly from Western Australia.

In order to cater for the greatest need first, the course is offered externally (by correspondence), and special consideration is given to teachers in remote areas of the State. Study will take between two and six years to complete, at the discretion of the student, and is equivalent to one year’s full-time study.

Approval is being sought for recognition of the course from the Australian Council on Awards in Advanced Education, as a Graduate Diploma in Aboriginal Education (PG 1), a qualification recognized throughout Australia and in most countries overseas.

Course content includes a coverage of traditional Aboriginal life, Australian race relations, Aboriginal social change, descriptive linguistics, sociolinguistics, Aboriginal speech, English as a second language, developments in Aboriginal education, compensatory education, ethnic education, teaching strategies and curriculum development. Opportunity will also be provided for developing a research or teaching project. Quotas have been placed on each unit.

Information and enrolment forms may be obtained by contacting the Principal of the College, in writing or by telegram.

(Education Circular, WA, December, 1974, p.377)

After only one month in their jobs, ATEP staff rose to the challenge by completing their first set of external notes, which were then typed, copied and posted (by snail mail) by the ATEP Secretary, under the supervision of Publications Officer Ed Brumby, to teachers all over Australia, many in remote towns and Aboriginal communities. It must be remembered that in those times technological support such as computers, mobile phones, emails or the internet was not available, so tasks were laborious and time consuming. Very remote teachers had to wait for weeks for their assignments or library book orders to arrive, by infrequent postage, and similar delays in returning those items.

Enrolment numbers in this new graduate diploma rose from 58 in the first year (1974), to 95 (1975), 104 (1977) and 115 (1980), making a significant contribution to professional development of teachers of Aboriginal children across WA, as well as to the reputation of Mount Lawley College of Advanced Education, and its income.

ATEP staff organised an on-campus week each year to enable those teachers who could, to come to Mt Lawley Campus and benefit from the human, educational and technological resources which were made available to them. In the first year of the course (1974), 25 teachers attended, most from remote schools (MLCAE Annual Report, 1974). They discussed issues with staff and other teachers, interacted with lecturers and visiting speakers, used print and media resources in the campus library, and were assisted in person with difficulties they were having in the course. This was a week of extensive networking and exchange of ideas across states, regions, types of school systems, variations in schools and personal philosophies.

Supported Group Intake for Training Aborigines as Teachers

A first in Australia in 1976, at Mt Lawley CAE, was a supported group intake of Aboriginal students (known as the Aboriginal Student Teacher Intake or ASTI), or later the more general Aboriginal Supported Group Intake), at Mt Lawley CAE.

In 1950, Western Australia had not one Aboriginal teacher or university graduate. During the next ten years the National Union of Australian University Students monitored Aboriginal education and offered University scholarships for high achieving Aboriginal students. Western Australia got none. The first national census to include all indigenous Australians revealed only 76 indigenous teachers in Australia in 1971.

In 1975, John Sherwood estimated that there were only about 8 qualified Aboriginal teachers in WA in a total teaching force of over 12,000, and in 1979 still less than 10 (Sherwood, 1979, p.501). In 1973 and 1974, he had observed two Aboriginal students, each potentially very capable of passing, withdraw from the course in their first year, due to various cultural and social reasons, including racism within the college and in the community.

After extensive national and state advertising, applicants were assessed with a specially designed, culturally appropriate test and then interviewed by the Aboriginal Advisory Committee of MLCAE. These students had to meet every academic and performance requirement of the Diploma of Teaching, so that on graduation they could perform as well as any other beginning teacher.

ASTI provided them with special support services, in a special on-campus centre, with a coordinator who organised all recruitment, testing, support, residential accommodation, counselling and liaison with Aboriginal people and academic staff. The first ASTI Coordinator was Eileen Willis, followed by Eversley Ruth (Mortlock).

The group intake model in Mt Lawley CAE (later WACAE and then Edith Cowan University), increased its Aboriginal teacher graduates from 14 to 35 in just 10 years, and to 213 by 2016. After recognising the success of ATEP’s supported group intake in dramatically increasing the number of qualified Aboriginal teachers, the National Aboriginal Education Committee (NAEC) announced a national target of 1,000 Aboriginal teachers in Australia by 1990, and urged that the Mt Lawley model be considered by universities across Australia, to achieve this target. Within a decade, most universities around Australia implemented this model.

A major research report was published on the first four years of this project (Sherwood J, et al, Training Aborigines as Teachers, 1980), and later Simon Forrest and Colleen Pead evaluated the first ten years of the Aboriginal student support group (Forrest, S and Pead, C, The First Ten Years, 1986). The latter authors acknowledged that such group intakes gave Aboriginal people the opportunity to excel, and reported that the success at Mt Lawley CAE became the model for “almost every tertiary institution in Australia.” Having a group intake allows peer support for all members, and justifies a full time coordinator to provide a range of supports.

It is ironic that having developed this successful model for Aboriginal university education in Australia, Edith Cowan University later abandoned it, while many other universities continue to apply it to continue the increase in Aboriginal graduates in an ever-widening list of undergraduate and postgraduate courses.

Bachelor of Education and Conversion Course to the Diploma of Teaching

ATEP introduced a series of units constituting a major in Aboriginal Education in the newly approved Bachelor of Education degree for qualified teachers wanting to upgrade their qualifications. Enrolments were on-campus as well as external studies, to assist teachers in remote schools.

Kath Lymon (1978) heard about this degree course in Aboriginal Education while studying the Conversion Course to the Diploma of Teaching, and enrolled in a Major in Aboriginal Education her B.Ed.

She writes:

“In my earlier teaching in Narrogin WA, I taught many Aboriginal children and was very aware of some of the economic, educational and social disadvantages they faced, but felt I did not know enough about their culture, or to make adjustments to the prescribed curriculum, to make a significant difference in educational outcomes. As I then spent time teaching in Africa I became more aware of my lack of understanding of Aboriginal culture.

I taught many indigenous children who were hospitalised when I taught in, what was then, Princess Margaret Hospital. I had numerous interactions with parents, many of whom were from the far north or far from home in a strange environment.

When working in the Education Department’s Audio-Visual Education Unit I visited a remote community to research and script a video program about the five language groups and the integrated language and culture program at the school, that involved community members working with teachers. I later returned with a video crew to work with the elders and the school to record the daily interactions.

When working in the Social Justice Branch of the Education Department, I helped develop the Social Justice Policy which included policy for Aboriginal students.”

Another means of providing qualified teachers with special background in Aboriginal Education was in the Diploma of Teaching (Conversion) course, which upgraded the two year Teachers Certificate held by most primary school teachers, to a three year Diploma of Teaching. Large numbers of WA teachers took up this opportunity, and ATEP offered a series of units in Aboriginal Education, Anthropology and Linguistics within this course. Those who enrolled were assisted in their immediate teaching situations, or for transfers into predominantly Aboriginal schools.

Pre-tertiary Courses by External Studies (AEEC AND GEC)

The process of establishing the supported group intake for Aboriginal students highlighted a need for a course to give Aboriginal people throughout WA the educational prerequisites to gain enrolment into higher education courses, because at that time very few had those prerequisites. To achieve this, another Australian first was in the form of a formal pre-tertiary course, with paid local tutors, offered by external studies to enable all students to continue to live and work in their home communities while studying.

Completing the Advanced Education Entry Certificate (AEEC) course qualified the student to enrol in selected courses in colleges of advanced education, or helped gain a higher level of employment. ATEP appointed Doug Hubble as AEEC Coordinator in 1977, and 60 Aboriginal people enrolled in 1978, with increasing numbers from all over Western Australia in subsequent years. In Hubble’s M.Ed dissertation (1986, p.33), he notes that in 1979 enrolments had risen from 60 to 104 statewide, and by 1980 were 150 (1986, p.34).

An evaluation of the AEEC course in its first year (1978) showed that some Aboriginal people needed a more basic education before they could succeed in the AEEC. The General Education Certificate (GEC) course was therefore designed and offered externally, using the same model as the AEEC, but with more basic educational content, appropriate to the reduced educational levels of many Aboriginal people in communities. The AEEC course could therefore concentrate on those assessed as having potential to qualify for advanced education studies.

The GEC was started in 1981, with Doug Hubble as Coordinator, and by the following year, enrolments in both AEEC and GEC courses was about 200, supported by 70 local tutors (1986, p.39). Over the years, Aboriginal people could choose to enrol directly into a diploma or associate diploma, or the AEEC or the GEC, depending on their education competencies and life goals.

In 1982 a Review Workshop of diverse stakeholders was held to evaluate both the AEEC and GEC courses. Positive and negative outcomes were analysed, solutions to problems proposed and as a result, objectives of the two courses were re-written (Grimoldby and Hubble 1983).

Hubble (1986, p.33) records that graduates of early years of the AEEC course enrolled in nursing (WA School of Nursing) and the BA in Social Sciences in the WA Institute of Technology (WAIT), as well as in different courses in Mount Lawley CAE. The number of different courses studied by AEEC graduates increased over the years.

Off-campus Centres for Training Teachers

ATEP staff and the Aboriginal Advisory Committee of the college soon became aware that training all pre-service teachers in Perth would prevent many Aboriginal people from remote areas from entering the profession. In another Australian first, an Off-Campus Centre model was designed for training teachers in large regional towns so that they could stay in or near their home communities to study. It was decided that a mixed group would be best for several reasons, so most of the students selected were Aboriginal, while a few were non-Aboriginal. Locations included Broome, Carnarvon, Kununurra, Kalgoorlie, Port Hedland and Geraldton. Broome was the first location, for four years, to allow students to spread their three year Diploma of Teaching if they needed to. Such was its immediate success, that a second centre was started within two years, in Carnarvon, so that two operated simultaneously.

The supportive response of local communities as well as the enrolled students was immediate and encouraging. A Coordinator, Jo Taylor, was appointed to the Broome Centre. Suitable premises were found, applications from intending students (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal) were received, interviews held, and offers of places in the course made.

The graduation rate was comparable with that of similar programs in WACAE Perth, and the Off Campus Centre model was found to be successful in the significant increase in the number of Aboriginal teachers in WA. Doug Hubble and Norma Morrison administered these centres in addition to the AEEC and GEC pre-tertiary external courses.

Special commendation is due to Doug Hubble for his vision, energy and effectiveness coordinating the AEEC and GEC courses and the Off Campus Centres for all those years, improving the education of many hundreds of Aboriginal people, enabling them to study in their communities, and changing their paths into the future.

Lyn Rodriguez (now Henderson-Yates) was a student in the AEEC course while living in Derby. Upon graduation, she enrolled in the Diploma of Teaching through the Broome Off-Campus Centre. She exemplifies how the AEEC course fulfilled one of its key objectives, that of qualifying Aboriginal students to enrol and succeed in an advanced education course. After starting the AEEC in Derby in 1978 and then graduating, Lyn enrolled in the Diploma of Teaching in the Broome Off-Campus Centre, with special permission to study in Derby.

She writes:

“I wanted to grow and expand beyond what I had already experienced in Derby. Once I started learning about Aboriginal history, I was hooked on wanting to make changes for us.

Having access to the course and completing it opened up so many doors for me. I was the first in my family – and extended family – to go to university. I knew that there was another world outside of Derby that I could explore. It began my lifelong work in Aboriginal Affairs. I have not worked in any sector apart from the Aboriginal Affairs sector. Using the tools I learnt way back then has helped me to continue my advocacy work in Aboriginal affairs. In 43 years of working in Aboriginal education, community engagement, management and leadership, I have never had long service leave because I prefer working for Aboriginal causes that satisfies my need to help make a difference“.

Lyn went on to become Deputy Vice Chancellor of University of Notre Dame Australia (UNDA) Broome Campus, as well as holding Indigenous Education leadership roles across UNDA Fremantle and Sydney. She established and was the foundation Director of the UNDA Nulungu Research Institute in Broome. Until late 2021, she was Chief Executive Officer of Derby Aboriginal Health Services and a Board member of the School Curriculum and Standards Committee. She continues working in research and PhD supervision, having previously been a PhD examiner.

Mount Lawley CAE’s Links with Strelley Group of Schools

After visiting Strelley Station in 1974, John Bucknall was impressed that the big Aboriginal community of more than 500, which owned 5 stations in the East Pilbara, and had refused to allow their children to be educated in government schools. They rightly argued that their children would be exposed to a total European system, with no significant elements of their language, culture, values and people evident. For decades they had been asking for bilingual, bicultural education, with their own community members on the staff, and a curriculum approved by elders through a School Board. Education authorities repeatedly refused.

John spoke with elders and Don McLeod, their administrator on “whitefella” business, about possibilities for a community controlled bilingual bicultural school being started on Strelley and some of its stations and one desert community. John Sherwood, ATEP and Mount Lawley CAE were very supportive in a number of ways, of this innovatory and unique venture in Aboriginal Education in WA.

In 1975, three second year teacher education students did teaching practice placements at Strelley, despite it having no school. They were supervised by John Bucknall, who discussed with the leaders the process for applying for new Commonwealth funding to establish a group of Aboriginal independent schools on stations owned by the Strelley Community. John worked with Strelley’s head office staff and John Sherwood from Mount Lawley CAE, to write a submission for funding. It was titled “Submission for a Special Grant to Establish a Bilingual School at Strelley Station, WA”. In it, John Sherwood offered the support of ATEP staff in advice and professional development in the running of the school. The submission was handed to the Commonwealth Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in his visit to Mount Lawley CAE to launch the 16mm colour movie “The Jigalong Mob”.

In 1975 the Department of Aboriginal Affairs approved all the requested funding for the Strelley Community School, and John Bucknall was offered the position of Education Coordinator (Principal) and his wife Gwen of Teacher Linguist. Towards the end of 1975 John resigned his lectureship in Aboriginal Education in Mount Lawley CAE, and opened Strelley School in February 1976 (Bucknall, 1982, p81-94). He had arranged for the three students who did a two week teaching practice placement at Strelley the previous year, when there was no school, to come back for their ten week Assistant Teacher Program in the school which had started only a few months before.

As promised in the funding submission, Mount Lawley gave many types of support to Strelley Community School. John Sherwood and other staff presented at professional development sessions and in-service courses for teachers, students did placements each year, John wrote papers on the unique education being offered at Strelley and evaluations, made videos of the schools, and took leave to relieve John Bucknall for 1983, when he and Gwen were burnt out from the years of exhausting, non-stop work. The close relationship between Mount Lawley College and the Strelley Group of Schools continued over the years

Aboriginal Lecturers Appointed

Is there a photo of the late Vic Forrest to insert here? If not, I can locate one.

As a strategy for increasing Aboriginal involvement in the college and its courses, Victor Forrest was appointed as Lecturer in Aboriginal Studies in Mount Lawley CAE, the first such position in any higher education institution in WA, and one of the very first in Australia. His impact was immediate, at both student and staff level. Students had the benefit of Aboriginal input and exchanges, some regularly in his own classes, and others shorter term, in his guest lecturer capacity. Staff had the new experience of an Aboriginal colleague in the staff room, in staff meetings and in general college activities.

Simon Forrest was the second Lecturer in Aboriginal Studies, and writes about his experiences as follows.

“I started as a student as part of the 2nd ATEP intake of Aboriginal students in 1977. Graeme Gower, Robyn Collard, Sandra Harris, Lindsay Grant and his daughter Krishna were all part of that cohort. Graeme and I met in the ML library, and developed a close friendship that continues today. I see others from those student days from time to time.

I really didn’t know what I was getting into in applying to become a teacher through ATEP. Teaching as a career was never on my radar. I remember in the early weeks of first year, driving my car off campus to a park nearby to eat my lunch. I think that was because I was a little shy and didn’t really know anyone apart from Graeme, and he was a relatively new friend.

As I got used to it more, and developed my friendship with Graeme, I stayed on campus much more. Use of the ATEP student building, resources and Eileen Davies as tutor also helped me settle in immensely. Graeme and I were in the same first year home group 1A. From memory there were only 5 men in a class of 20 or so. Due to this, Graeme and I became good friends with 2 of the other three guys. There was a request from the Phys Ed department for anyone interested in playing for the college football team, so I signed up. This enabled me to meet a wider group of males as football team consisted of males from first year through to third year. Some of these friendships from the football team continue today.

ATEP was there to support Aboriginal students as a group, which created a very helpful environment for us. I didn’t experience any racism or racist comments, certainly not to my face as a student. I think non-Aboriginal students were generally supportive of the Aboriginal student cohort. Over the three years Graeme and I developed strong friendships with a relatively small group of fellow students, all non-Aboriginal. These close bonds remain today over 40 years later as the group meets up on a regular basis.

I think the Diploma of Teaching, back in the day. was a good preparation for primary teaching. The teaching practice component in first year was significant for me as a person who never thought of teaching as a career. Spending part of one day each week in an allocated school and classroom, and then doing the 2-week prac in that class, was a great introduction to teaching. It allowed you to be a part of the school and enabled you to develop relationships with children and staff in the school. Some of the core units especially in 3rd year did not necessarily assist in preparation for a teacher.

My first teaching appointment was to Cundeelee Remote Community School some 300km east of Kalgoorlie, north of the trans Australian Railway Line. While I had been on Aboriginal reserves in some SW towns, staying with relatives, I had never been to a remote community. At the time I didn’t think too much about teaching there as a Nyoongar person raised in the city and now being involved in a tradition-oriented community. But being there and making friends and witnessing ceremonies was, when I look back, a very significant time for me personally, culturally and professionally and an experience I will remember always with significance. The other teachers at the school were the principal and his wife and they had 2 children, one of whom was in my class. They also had a significant impact on me personally and professionally. I will be forever grateful for their friendship and support.

My second posting was to Kellerberrin District High School. I wanted to teach in schools with significant numbers of Aboriginal children. This was a totally different experience from Cundeelee. I experienced significant racism from within the non-Aboriginal community from the very first day I arrived, but not at the school. Actually, I witnessed the town’s racism on my way back to Perth from Cundeelee and visited the hotel for a drink. Not to my surprise, there was small a black bar with a wall separating it from the public bar and I ended up drinking my beer with a Nyoongar man in the black bar. There is a story to be told about my first visit to the Kellerberrin Hotel, but at another time. There were regular incidents of racism over the two years I was at Kellerberrin. Despite this, I made some good and lasting friendships at Kellerberrin, including teachers and Aboriginal Education Officers at the school.

I started at WACAE (Mt Lawley Campus) in September 1983 as a Lecturer. The position was previously held by my uncle, Victor Forrest. He relinquished the role to take up a position as a research officer with the National Aboriginal Education Committee (NAEC) that was chaired at the time by Stephen Albert from Broome. Peter Reynolds was Relieving Head of ATEP at the time, as John Sherwood was on his third year of leave up north, that particular year as coordinator of the Strelley Group of Community Schools in the East Pilbara.

I remember my office was adjacent to the small staff room and next to Lois Tilbrook’s office. I also remember my first outside phone call which was from a friend from student days ringing to congratulate me and the reason I remember is I didn’t know what to say in answer the phone. I remember seeing Uncle Victor answer the same phone once before and his greeting was “Forrest here” so I stumbled through with “um ah ah um ah Forrest here”.

Growing up we never had a phone in our house, and this was my first office with my own telephone, that I had never ever had before. I also think about a story my Mum told me about her time when she left New Norcia and went to work as a domestic for a family. The first time she was left alone in the house, the phone rang. She didn’t know what to do so, as she had no experience using a telephone, so she ran outside and sat in the fig tree eating figs, but the phone kept ringing. She eventually plucked up enough courage to pick up the phone and listened. It was the father of the family she was working for, and he was calling to see how she was going.

Starting my Lecturing role in September was ideal. Teaching allocations were already in place for the semester, so I was introduced to the role by sitting in on other lecturers’ classes and tutorials, to see how they went about things. The following semester (1st semester 1984) I recall being allocated a part time teaching load and doing other things introducing me to the role. By 2nd semester 1984 I had a full time teaching load. I was doing classes, tutorials and even a few mass lectures at all the campuses of WACAE, but mainly Churchlands and Claremont. I also visited and assisted the ATEP centre at Nedlands.

Lecturing continued full time, and in 1985 John Sherwood as Head of ATEP appointed me to commence later in the year as Senior-Co-ordinator of Aboriginal Programs (responsible for the Aboriginal centres on each of the WACAE campuses). In 1988 I took leave and taught at Rangeway Primary School, returning to full time lecturing role in 1989. Leading up to the establishment of ECU in 1991 was an interesting time in Department of Aboriginal and Intercultural Studies (DAIS) as there were two parts: the higher education teaching part and the Aboriginal Programs part, including Aboriginal external pre-tertiary courses, off campus centres in regional towns, and Aboriginal student support centres on each WACAE campus, including Bunbury.

There were meetings at Churchlands campus chaired by then Director of WACAE, Dr Doug Jecks, about the organisational structure of the new university, and he said to me in one meeting “Why don’t we split DAIS into two? This would continue the tertiary teaching as one department, and all those Aboriginal programs can be together, and you can have your own department”. That was the beginning of the Department of Aboriginal Programs that became a Kurongkurl Katitjin School of Indigenous Australian Studies in its own right in around 1994 or 1995. I was appointed as the Inaugural Head of School and remained in that position until early 1998 when I resigned and moved with my family to Geraldton.”

Simon later became Associate Professor and Head of Kurongkurl Katitjin School of Indigenous Australian Studies in Edith Cowan University, later Emeritus Professor in Curtin University, and now in retirement is an active Nyoongar Elder.

This chapter described the many Aboriginal courses and projects which started at Mount Lawley College from 1974. Chapter 10 covers the introduction of Migrant Studies and the diversification to Intercultural Studies and new structures.